The monetary regime has immediate consequences for our behavior—as individuals, institutions, and financial entities.

One underappreciated victim of the fiat age is long-dated bonds. When price predictability of the money is strong, and commitment to the monetary regime is credible, you can finance projects or business ventures over very long time frames—especially if you think those ventures or institutions will be around by then.

Universities serve as perfect illustrations. Whatever the troubles in higher ed these days, most elite universities are probably fine: They have weathered worse.

Case in point, my alma mater, University of Oxford, has had some form of higher education teaching since 1096, its oldest colleges having existed since the 1250s.

Oxford has seen everything—wars, famines, changing rulers, religious wars, population increases, industrialization, globalization, and certainly many different sorts of monetary shifts.

It’s fair to bet they’ll be around in a decade or a century; financing their operations (maintenance, build-outs, facilities, etc.) with long-duration debt thus makes sense—morally and economically. Most such facilities will benefit several generations of students and scholars, and so it’s reasonable to spread out the expense over time.

If the money works to faithfully reflect underlying economic reality, which allows for the price system to work its magic, everyone involved can plan for such expenses.

Under gold, aggregate prices are mean-reverting, and so we know that $100 tomorrow or a century hence buys roughly what $100 buys today. (According to a famous Wall Street adage, an ounce of gold bought a man a high-quality suit across all ages.)

Making debt contracts becomes simple and transparent: $100 borrowed at X% interest a year, repaid in a decade or a century, means the borrower gets funding and the creditor gets x% predictable return on their investment.

When the money isn’t working, as is the case under fiat, there is no such long-term price predictability.

You’re always living in financial terror, waiting for the inflationary sword of Damocles to drop; when it does, it completely undermines your finances and ruins profitability calculus for decades (the “dangers of duration,” Financial Times journalist Robin Wigglesworth calls it).

Ergo: nobody issues long-term debt, and every institution—from banks and corporations to universities and governments—is stuck constantly rolling over debts at new and hopelessly variable rates…

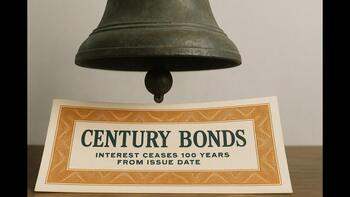

…except something strange happened in the 2010s. As central banks were tripping over themselves to push interest rates lower and lower—not even zero stopped them—“century bonds” returned to the world of finance.

Whether by greed or simply eye-popping, unprecedentedly low rates, people forgot that there was a monetary regime reason why the once-thriving market for long-dated bonds had more or less vanished.

So Mexico, Argentina, and Austria issued century bonds, as did many universities and large corporations. In 2017, Oxford placed a three-times oversubscribed century bond at 2.5% interest. (MIT, having been too early to the party, issued $500m at 3.885% already in 2016.)

That was just simple bond math: When money is completely free, investors salivate at the prospect of earning 2.1% from a calm, reputable, fiscally conservative European government.

When inflation started to reassert itself, the bond traded at well above 200. The story from then on was a drawdown worthy of Bitcoin’s worst episodes: -73%—on a safe, government bond!

Mid-pandemic, Austria even returned to the yield-hungry bond markets and placed another century bond at 0.85%, in a move that was fiscally ingenuous but morally almost criminal.

While the printers were running at full pace, they took money from investors—money they must have known would be worth much, much less when finally repaid in 2120, let alone after the fresh euros had bid up the prices of consumer goods by some 15-20% just a few years thereafter. (Today, the Oxford and Austria bonds trade at 56, 66, and 36, respectively—significantly below par, let alone what they were at their peak in 2021.)

Having already financed government expenditures or a new university research center at a low single-digit percentage interest cost when inflation roared to upward of 10% was like getting a corresponding discount on their outlay—after the fact.

They got somebody else’s labor and resources for less than what they were worth by the time the projects were finished.

Wigglesworth again: “There are few better examples of the explosive power of duration when the interest rate cycle turns.”

None of this is to lament the tragedies of bond investors or to cherish the fiscal ingenuity of government or university finance directors, but to illustrate the hopelessness of planning finances under fickle monetary regimes.

In the 2010s, during the era of extremely loose monetary policy and “there is no alternative,” there was nowhere to place savings but the stock market, or venturing further and further out the duration curve for bonds.

In the 2020s, after the turbulence of COVID policies and a transformation of the stock market into the Magnificent 7 show, those very same “safe” government bonds became exceedingly risky. (Silicon Valley Bank in 2023!)

Anyone who put their funds in Austria’s or Oxford’s century bonds in recent years must wait a very long time to nominally get their funds back; in real terms, they probably never will.

Interestingly, Dr. Judy Shelton, economist and proponent of sound money, has recently suggested long-term, gold-backed “Treasury Trust Bonds.”

Making financial decisions (borrowing and lending, saving and investing) for periods such as a lifetime or retirement requires extreme faith in the stability of fiscal/monetary conditions—not to mention the political institutions and arrangements themselves!

A friend once put it to me that relying for your retirement on tax-favored accounts and investing rules currently in place implicitly trusts the next ten Treasury Departments not to cheat you—or the next half-dozen Fed chairpersons to responsibly steward the dollar’s monetary policy. That’s a tall order.

By holding cash, bonds, bank deposits, CDs, or a plethora of various financial instruments to carry value forward in time, you’re hoping—against all evidence—that the guardians of the fiat monetary system’s levers won’t unleash more bouts of inflationary madness on you.

Good luck with that.

Financial markets learned some form of lesson on century bonds and duration in the last fifteen years: One cannot sensibly have long-duration credit assets under fickle, unpredictable money.

Until we have better money (i.e., sound money), I doubt we’ll see many more century bond offerings.