President Ford inked a consequential executive order on New Year’s Eve in 1974

Gold enthusiasts can celebrate a golden anniversary on New Year’s Eve and simultaneously mark a market manipulation milestone.

Fifty years ago, President Gerald R. Ford legalized private gold ownership, allowing Americans once again to stack the regal metal as a wealth-preserving asset and safe haven against monetary inflation and currency debasement.

Gold futures trading and market meddling also began in the United States a half-century ago.

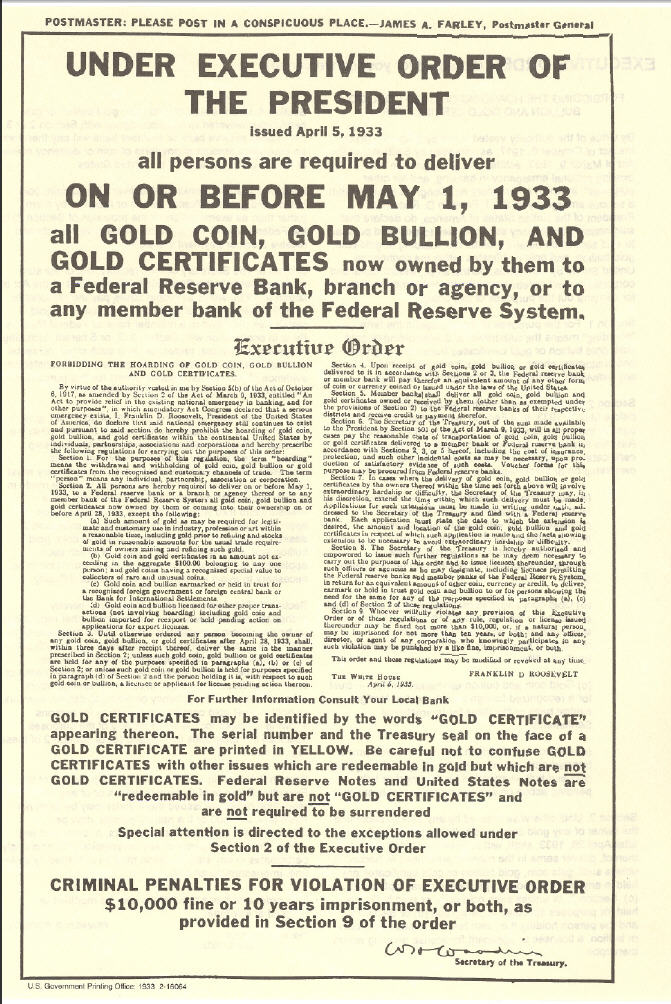

On Dec. 31, 1974, Ford issued an executive order revoking President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s 1933 decree that criminalized gold hoarding and prohibited American citizens from owning more than $100 worth (5 troy ounces at the time) of the demonetized metal.

President Ford signed the order without celebratory remarks or public fanfare. He simply released an official statement citing the legal authority he had to take the action.

Americans Could Buy Gold Again Without Risking Prosecution

While no confetti flew or champagne corks popped in the White House to mark the momentous occasion, repeal of FDR’s 41-year-old edict sparked the largely dormant gold industry and restored trading of the yellow metal as a commodity.

Gold could be owned, bought, and sold domestically as an investment without risking a $10,000 fine and 10 years in prison. Gold coins weren’t U.S. legal tender at the time, and bullion wasn’t used in official foreign exchange after President Richard Nixon delinked the dollar from gold in 1971.

As the nation’s only unelected president and vice president, Ford didn’t have a political or public mandate to legalize gold. Nor was he a fervent goldbug or hard-money proponent.

Mr. Nice Guy, as the nation’s 38th president came to be known, merely went along with a bipartisan measure passed by Congress four months earlier. The no-name bill—Public Law 93-373—permitted “United States citizens to purchase, hold, sell, or otherwise deal with gold in the United States or abroad.”

Introduced by Sen. James Fulbright (D-Ark.), the legislation was approved by a coalition of Democrats and Republicans following a grassroots movement led by James U. Blanchard III, founder of the National Committee to Legalize Gold.

The measure’s passage was attributed to support from free-market gold advocates and its link to a foreign aid package promoted by Nixon. Ford signed the bill into law on Aug. 14, 1974, six days after the partial-term Republican took the presidential oath following Nixon’s resignation over the Watergate scandal.

Gold legalization wasn’t without its concerns and opposition. The decision raised alarms within the U.S. Treasury Department and Federal Reserve, particularly after the gold price climbed to a record high, topping $195 an ounce on Dec. 30, 1974.

At the time, the statutory gold price was $44.22 an ounce, and the nation’s gold stocks were undergoing a highly publicized audit that began with a congressional, media-covered, and question-raising inspection of a single vault at the Fort Knox (Ky.) Bullion Depository on Sept. 23, 1974.

U.S. Treasury & IMF Sold Gold to Cap Price

Treasury officials worried strong public demand for gold might drive prices higher, increase the nation’s trade deficit if the commodity were imported, and further weaken the unbacked, devalued, and expanding supply of Federal Reserve Notes.

Those were valid concerns amid the inflationary spiral triggered by Nixon’s suspension of the international gold standard, the lingering effects of the 1973 Arab oil embargo, and persistent federal budget deficits and rising national debt.

To contain the price, the Treasury announced plans to sell 2 million ounces of gold bars. The first auction was held on Jan. 6, 1975, less than a week after Ford legalized private gold ownership.

With a subsequent sale on June 30, a total of 1.25 million ounces of gold were sold at prices ranging from $153 to $185 an ounce. Sales of 25 million ounces of International Monetary Fund (IMF) gold commenced in 1976, and Treasury sales of 15.8 million ounces resumed in 1978 to curtail prices and defend the ailing U.S. currency.

U.S. Bullion Depository (at Fort Knox, KY)

Federal Reserve Chairman Arthur Burns called Congress’ decision to remove the ban on private gold ownership “ill-timed” and urged a delay.

Burns feared investors might withdraw funds from savings accounts and sell stocks to buy gold, causing extreme price movements, widespread speculation, and financial market disruptions. He also expressed concern that U.S. Treasury gold sales aimed at controlling the price might require future interventions.

“Once some Treasury sales have been made, it might be difficult to resist pressures for further intervention in the future—either to support the price or to keep it from rising,” Burns wrote in a Nov. 13, 1974, letter to Treasury Secretary William Simon.

Within a few months, Burns negotiated a deal to restrict official gold purchases and restrain gold prices. A declassified letter, dated June 3, 1975, confirms Burns’ clandestine intervention.

“I have a secret understanding in writing with the Bundesbank [German central bank], concurred in by Mr. [Helmut] Schmidt [West Germany's chancellor at the time], that Germany will not buy gold, either from the market or from another government, at a price above the official price of $42.22 per ounce,” Burns wrote to Ford, who ostensibly was agreeable to the confidential agreement as no evidence has emerged to suggest otherwise.

“I am convinced that by far the best position for us to take at this time is to resist arrangements that provide wide latitude for central banks and governments to purchase gold at a market-related price,” Burns added.

Gold Futures Market Intended to Increase Volatility, Reduce Demand

Various forms of market manipulation and price suppression have been ongoing since gold futures trading opened on the COMEX in New York and four other U.S.-based commodity exchanges on Dec. 31, 1974, which coincided with Ford’s executive order rescinding the ban on private gold ownership.

A telegram sent to the U.S. Secretary of State from the U.S. Embassy in London, England, on Dec. 10, 1974, revealed the importance of gold sales and futures trading.

In the telegram, presumably written by the embassy’s Deputy Chief Ronald Spiers, London gold dealers are described as praising the announced sale of 2 million ounces of U.S. gold and predicting deregulation of—and volatility in—the futures market would reduce demand for physical metal.

“Each of the dealers expressed the belief that the futures market would be of significant proportion and physical trading would be minuscule by comparison,” reads the cable released by WikiLeaks.

“Also expressed was the expectation that large-volume futures dealing would create a highly volatile market. In turn, the volatile price movements would diminish the initial demand for physical holdings and most likely negate long-term hoarding by U.S. citizens.”

Despite fears, opposition, and market meddling, the ability of Americans to own gold revived the retail and wholesale gold business in the United States beyond the dental, jewelry, and collectible coin trade, which were exempt from Roosevelt’s 1933 prohibitive edict.

In anticipation of legal gold ownership, pre-1933 gold coins returned from overseas. Bullion dealers built or leased vaults to store gold. Private mints launched or expanded operations to produce gold rounds and foreign coins.

Coin shops opened from coast to coast to meet pent-up public demand for gold as a hedge against currency debasement and price inflation. The sleepy gold industry was awakened from its four-decade slumber with the stroke of President Ford’s New Year’s Eve pen.

The consequential event warrants a toast to 50 years of legalized gold.

Englert is the author of “Rigged: Exposing the Largest Financial Fraud in History.”