Last week marked the 100 year anniversary of the end of the Weimar inflation in Germany. In last week's newsletter I wrote about my base case for the next couple years, which is that we're repeating the 1970's stagflation under Jimmy Carter.

This week I want to talk about one of the worst case scenarios, hyperinflation.

Hyperinflation

The German hyperinflation after World War I is probably the most talked-about hyperinflation today.

Of course, paper money has been hyperinflated many times, starting with its first inventors in Song Dynasty China a thousand years ago, when government first realized they could cheaply mass-produce paper money.

Argentina, famously, is currently undergoing 143% inflation. Which was a key reason for libertarian Javier Milei's win last week.

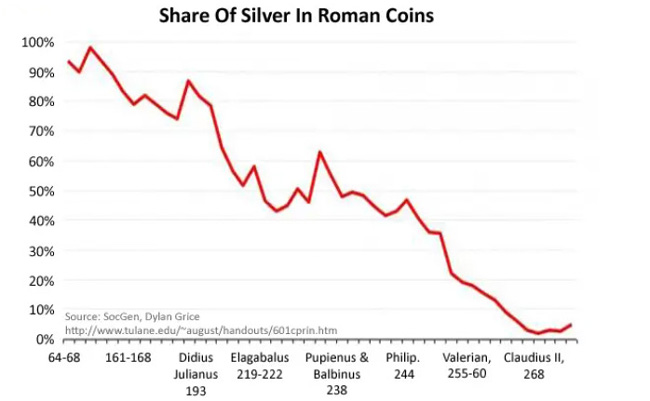

Even before paper, governments have been hyperinflating currencies for millennia. Typically by melting the silver, gold, or copper coins that individuals produce and use, then recasting them with base metals.

They would keep the leftover silver, effectively seizing it, and mandate acceptance of the new coins at the artificial value – typically on pain of death. The late Roman hyperinflation of Diocletian gets the press, but in fact the Romans frequently debased the main Roman coin – the denarius – for centuries. Starting just 11 years after it was officially recognized.

The Weimar Hyperinflation

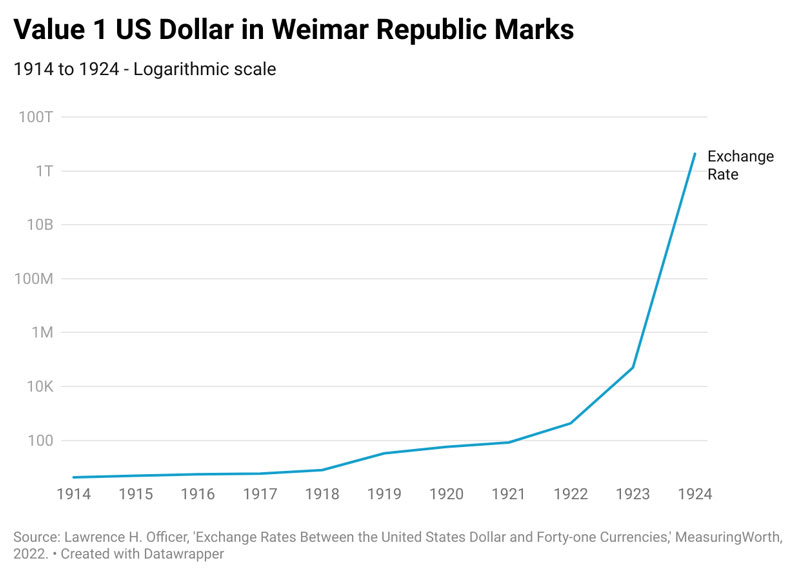

Returning to Germany, the gold-backed mark had been the official money of Germany ever since its unification in 1871. When World War I started in 1914, the German government took the mark off gold to run enormous deficits for the war. Total public debt went from 5 billion marks in 1914 to 105 billion in 1918, at the end of the war.

A large fraction of this was funded by the German Central Bank, the Reichsbank, driving up the money supply – the amount of money in existence – from 6 billion marks to 33 billion marks in just 4 years. This drove a 115% inflation over the period, as the mark dropped 6-fold against the US dollar, which was still gold-backed.

115% in 4 years was rough – about 20% per year. But that was just the beginning.

This is because the war had wiped out nearly half of Germany's industrial production, and the victorious allies made Germany pay 132 billion marks in reparations. Scaled to our modern money supply, that's equivalent to the US owing $90 trillion in reparations on top of our national debt.

Despite these enormous financial burdens, after the war the new socialist government wanted to dramatically raise spending.

They first tried raising taxes, but that wasn't enough so they halted reparation payments. This led France and Belgium to seize Germany's main industrial region, the Ruhr. The socialist government encouraged workers to resist, promising to pay their wages.

This was the fatal bite from the apple. Starting in May 1923, the Reichsbank began printing on a truly epic scale: The amount of physical currency doubled in a single month, driving higher prices that the Reichsbank kept chasing with larger and larger issues.

Within 3 months the money supply grew 80-fold, from 8 billion in May to 670 billion by August. 3 months later it hit 400 quintillion – that's 400 billion billion.

Prices, of course, followed suit. A loaf of bread cost 200 billion marks – roughly double the national debt at the end of the war. A dollar bought 4.2 trillion marks.

There were stories of American exchange students in Berlin using their food allowance to buy up houses. Regular Germans would rush out on payday to spend the money before it inflated away by the end of the day. Housewives used bundles of marks as firewood.

As you'd expect, this savaged the economy. Unemployment rose to nearly 30%, and even the middle class was selling off assets – their pianos, their family heirlooms.

In the countryside, gangs of city folk invaded small towns, beating up farmers, killing their livestock out of spite, and stealing food.

There's an excellent book called When Money Dies by Adam Ferguson that goes through the misery, and you read more details at Thorsten Polleit’s excellent article at Mises.org.

The hyperinflation only ended when the central bank was forced to stop issuing new money to fund government deficits. Just days later, the key inflationist, Reichsbank President Rudy Havenstein, died. New president Schacht stabilized the mark, lopping off 12 zeros to restore the pre-war exchange rate with the dollar. The Reichsbank massively reduced new issues, so it stuck. The hyperinflation was over.

Lessons for Today

The main lesson of the German hyperinflation is that once a central bank becomes a tool to fund the government, hyperinflation becomes a permanent threat.

Like the Federal Reserve, the Reichsbank was independent on paper. But given governments always control central banks, they can never be truly independent.

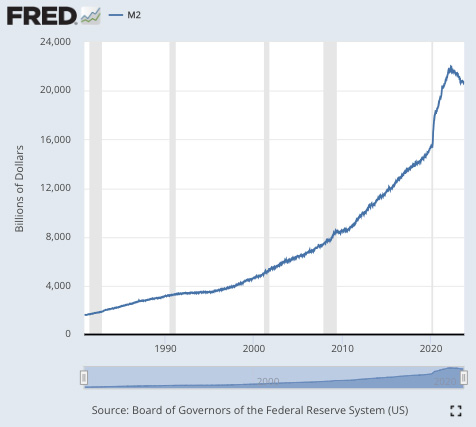

In just the past few years, during Covid lockdowns the Federal Reserve printed nearly $5 trillion to finance federal deficits. At one point one in three dollars had fresh ink.

This is a far sight from doubling the currency in a month, but it delivered what it always does – runaway inflation. Even on official statistics we hit nearly 10% inflation in 2021 and now, 3 years later, are still running inflation over twice the official target. With government deficits once again threatening to put the Fed back on the money printer.

US Money Supply

What's the solution? Simple: Separation of government and money.

Like those private Roman coins, individuals will coin money that holds its value – otherwise consumers won’t accept it. Only the state can hyper-inflate. And so long as the state controls the money it is always a catastrophe waiting to happen.

When it comes to paper money – indeed, all government money – we know how the book ends: It will hyper-inflate. It’s just a question of when.